Rebecca Lee Crumpler challenged the prejudice that prevented African Americans from pursuing careers in medicine. In 1864 she became the first African American woman in the United States to earn an M.D. degree.

Although little has survived to tell the story of Crumpler’s life, her medical knowledge is preserved in her book of medical advice for women and children, published in 1883. This is one of the earliest medical books published by an African American.

Crumpler’s early life

Dr. Crumpler was born February 8, 1831, in Delaware, to Absolum Davis and Matilda Webber. An aunt in Pennsylvania, who often cared for sick neighbors, raised her. This aunt’s example of service to the sick may have influenced her career choice.

By 1852 she had moved to Charlestown, Massachusetts, where she worked as a nurse for eight years, despite lacking formal training. (The first formal school for nursing opened in 1873). In 1860, she was admitted to the New England Female Medical College.

First African American woman in medical school

When she graduated in 1864, Crumpler was the first African American woman in the United States to earn an M.D. degree, and the only African American woman to graduate from the New England Female Medical College, which merged with Boston University School of Medicine in 1873.

In her Book of Medical Discourses In Two Parts, published in 1883, Dr. Crumpler summarized her career path:

“It may be well to state here that, having been reared by a kind aunt in Pennsylvania, whose usefulness with the sick was continually sought, I early conceived a liking for and sought every opportunity to relieve the sufferings of others.

Later in life, I devoted my time, when best I could, to nursing as a business, serving under different doctors for a period of eight years at my adopted home in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

From these doctors I received letters commending me to the faculty of the New England Female Medical College, whence, four years afterward, I received the degree of doctress of medicine.”

Caring for African Americans in the South

Dr. Crumpler practiced in Boston for a short while before moving to Richmond, Virginia, after the Civil War ended in 1865. Richmond, she felt, would be “a proper field for real missionary work”, and one that would provide opportunities for her to become acquainted with the diseases of women and children.

“During my stay there nearly every hour was improved in that sphere of labor. The last quarter of the year 1866, I was enabled . . . to have access each day to a very large number of the indigent, and others of different classes, in a population of over 30,000 colored.”

She joined other black physicians caring for freed slaves who would otherwise have had no access to medical care, working with the Freedmen’s Bureau, and missionary and community groups, even though black physicians experienced intense racism working in the postwar South.

When her service there was finished, she returned to her former home, Boston, where she continued practicing, especially with children, regardless of the families’ ability to pay her.

“Dr. Crumpler continued to work despite the extreme sexism, racism, and rudeness she experienced from colleagues and others to treat her patients. The discrimination these African American patients experienced encouraged an increasing number of African Americans to pursue medicine.”

Rothberg, Emma. “Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler.” National Women’s History Museum, 2021.

She lived on Joy Street on Beacon Hill, then a mostly black neighborhood. By 1880 she had moved to Hyde Park, Massachusetts, and was no longer in active practice.

Dr. Crumpler- medical author

Her 1883 Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts, is based on journal notes she kept during her years of medical practice. It is a remarkable achievement as a physician and medical writer in a time when very few African Americans were admitted to medical college, let alone published. Her book is one of the very first medical publications by an African American.

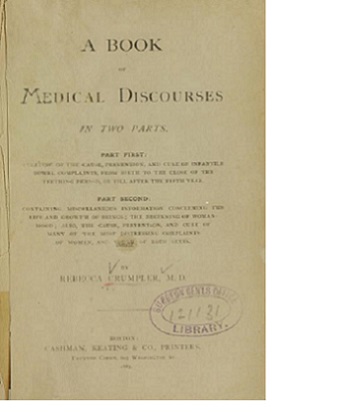

According to the cover page,

“Part first: treating of the cause, prevention, and cure of infantile bowel complaints, from birth to the close of the teething period, or till after the fifth year.

Part second: containing miscellaneous information concerning the life and growth of beings, the beginning of womanhood, also the cause, prevention, and cure of many of the most distressing complaints of women, and youth of both sexes.”

The book is considered to be in the public domain. You can view and download it at this link

National Library of Medicine Digital Collections

Front page of Dr. Crumpler’s “A Book of Medical Discourses.” There are no existing photos of her.

Public domain, courtesy U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Dr. Crumpler-wife and mother

Dr. Crumpler married twice and had one child, Lizzie Sinclair Crumpler. She died in Boston in 1895 and is buried in Fairview Cemetery there. Her home in Beacon Hill is featured on the Boston Black Heritage Trail, part of the Boston African American National Historic Site.

Her life and work testify to her talent and determination to help other people, in the face of doubled prejudice against her gender and race.

National Park Service

photos for illustration only

For this article, I used information from

- Changing the Face of Medicine, “Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine”

- Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, National Park Service,

- National Women’s History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/

Exploring the HEART of Health

I’d love for you to follow this blog. I share information and inspiration to help you transform challenges into opportunities for learning and growth.

Add your name to the subscribe box to be notified of new posts by email. Click the link to read the post and browse other content. It’s that simple. No spam.

I enjoy seeing who is new to Watercress Words. When you subscribe, I will visit your blog or website. Thanks and see you next time.

Dr. Aletha

Meet other trailblazing women physicians in this post

How Women Changed and are Changing Healthcare

The first woman graduate of a United States medical school was born in Bristol England in 1821. Elizabeth Blackwell came to this country as a child and originally had no interest in medicine. But when a dying friend told her, “I would have been spared suffering if a woman had been my doctor”, she found…

Keep reading