I live in Oklahoma, and depending on where you live you may or may not know where that is.

My state lies in the south-central part of the United States, often called the Plains. You may be familiar with Texas, a large state that shares its southern border with Mexico.

Oklahoma shares its southern border with Texas. We also border five other states-Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, and New Mexico.

With measles cases reported in Texas and New Mexico, it’s not surprising it has crossed over into Oklahoma. Rather, people infected with the measles virus have crossed over.

According to the CDC,

“As of March 6, 2025, a total of 222 measles cases were reported by 12 jurisdictions: Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York City, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, and Washington.”

Why should you care? Lots of people will travel over Spring Break, which starts here next week. In two months schools close for the summer and families travel on vacations. When people travel, the viruses they carry go with them.

More states, and maybe countries, may join the list of measles outbreaks. Here is the report from Oklahoma Voice about the infections in my home state.

First measles cases reported in Oklahoma, but public health officials remain mum on details

by Emma Murphy, Oklahoma Voice

March 11, 2025

OKLAHOMA CITY — State health officials on Tuesday ( March 11, 2025) said they’ve confirmed the first two cases of measles in Oklahoma amid an ongoing outbreak in Texas and New Mexico.

But Oklahoma State Health Department officials did not share where in Oklahoma those cases were diagnosed or how old the individuals are.

They said they believe the exposures were associated with the outbreak in Texas and New Mexico, which is confirmed to have killed one child and sickened over 250 people.

Erica Rankin, a spokesperson for the state health department, said Oklahoma’s two cases present “no further risk to public safety.” The agency only releases geographic information about measles cases when there is a “public health risk” and all potential exposures cannot be identified. Three or more related cases is considered an outbreak, she said.

It was unclear Tuesday afternoon whether the individuals were vaccinated against the measles.

Health officials did say the two cases are unrelated to an erroneous report of measles in Bartlesville on March 4. The two confirmed cases have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and are under investigation.

With outbreaks in neighboring states, the Oklahoma Health Department, or OSDH, has been on “high alert” and monitoring for cases in the state, according to a statement from the department.

“If a measles case is identified, the OSDH team will work with the individual on next steps and guidance to mitigate the spread and protect others. If there is a risk of spread to the public, the OSDH will notify the public and share any information necessary to protect the health of Oklahomans.”

“These cases highlight the importance of being aware of measles activity as people travel or host visitors. When people know they have exposure risk and do not have immunity to measles, they can exclude themselves from public settings for the recommended duration to eliminate the risk of transmission in their community.”

per Kendra Dougherty, the Health Department’s director of Infectious Disease Prevention and Response

Prevention

Measles can be prevented with an MMR vaccine which is recommended for children at 12 to 15 months of age and again at 4 to 6 years old. Receiving two doses of the vaccine is about 97% effective at preventing measles, and one dose is about 93% effective, the Health Department reported in a statement.

Almost 92% of Oklahoma kindergartners were up to date on their MMR vaccines, according to the 2023-24 Oklahoma Kindergarten Immunization Survey.

The department recommended that individuals with known exposure to measles who are not immune through vaccination or prior infection consult with a health care provider and “exclude themselves from public settings for 21 days unless symptoms develop.”

To confirm a report of measles, the case must show symptoms and have a test confirming the diagnosis.

This story is republished under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Oklahoma Voice is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Oklahoma Voice maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Janelle Stecklein for questions: info@oklahomavoice.com.

Measles elsewhere

Here are links to stories about the ongoing outbreaks of measles in New Mexico and Texas.

CDC Key Points about Measles

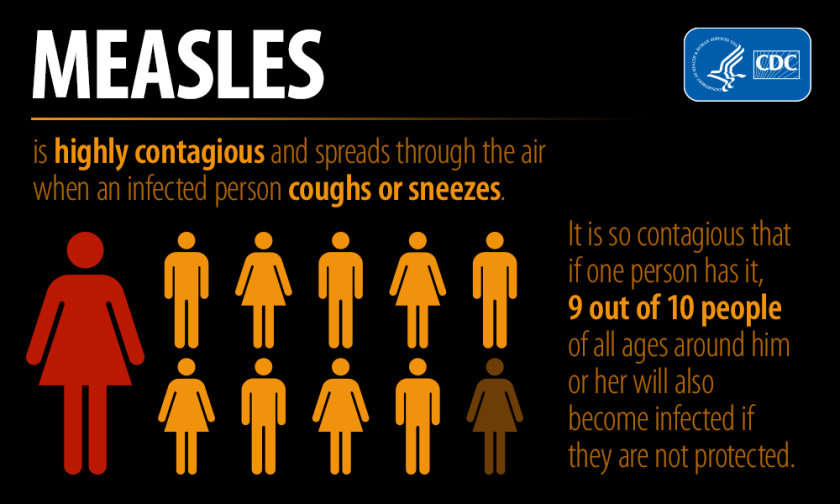

- Measles is very contagious and can be serious.

- Anyone who is not protected against measles is at risk.

- Two doses of MMR vaccine provide the best protection against measles.

Exploring the HEART of Health

I’d love for you to follow this blog. I share information and inspiration to help you transform challenges into opportunities for learning and growth.

Add your name to the subscribe box to be notified of new posts by email. Click the link to read the post and browse other content. It’s that simple. No spam.

I enjoy seeing who is new to Watercress Words. When you subscribe, I will visit your blog or website. Thanks and see you next time.

Dr. Aletha

- About Dr. Aletha

- How to Use this Site

- Make Your Life Easier

- Search by Category

- Share the HEART of health

- my Reader Rewards Club

- RoboForm Password Manager

Cover Image

The cover image of this post was created by JetPackAI available with WordPress.