In this post we’re learning how the federal government budget is created with the help of Julie Rovner at KFF.

I have gently edited the text for length and readability, added headings, and added notes in parentheses to clarify terms.

The cover image for this post was generated by JetpackAI, available on WordPress. (affiliate link)

The Federal Budget Process

Under Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, Congress is granted the exclusive power to

“lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts (tax or duty) and Excises,

the U.S. Constitution

and to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defense and General Welfare of the United States.”

. United States, 1862. N.Y.: C. Magnus, 12 Frankfort St. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2010648441/.

The 1974 Budget Act

In 1974, lawmakers passed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act to

- standardize the annual process for deciding tax and spending policy for each federal fiscal year (October 1 to September 30) and

- to prevent the executive branch from making spending policy reserved for Congress.

It created the House and Senate Budget Committees and set timetables for each step of the budget process.

CBO-Congressional Budget Office

The 1974 Budget Act also created the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). This non-partisan agency has plays a pivotal role in both the budget and the lawmaking processes.

The CBO issues economic forecasts, policy options, and other analytical reports, but most significantly estimates how much individual legislation would cost or save the federal government. Those estimates can and do often determine if legislation passes or fails.

President’s Proposed Budget

The annual budget process is supposed to begin the first Monday in February, when the President presents his proposed budget for the fiscal year beginning the following Oct. 1. This is one of the few deadlines in the Budget Act that is usually met.

. [New Orleans, Louisiana:publisher not transcribed] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2018756464/>.

Congress’ Spending Blueprint

The House and Senate Budget Committees each write their own “Budget Resolution,” a spending blueprint for the year that includes annual totals for mandatory and discretionary spending.

(Mandatory spending , required by law is also known as entitlement spending. Examples are Social Security, Medicare, veterans benefits, and interest on debt.)

Mandatory spending (roughly two-thirds of the budget) is automatic unless changed by Congress.

The budget resolution may also include “reconciliation instructions” to the authorizing committees overseeing those programs to make changes to lower the cost of the mandatory programs in line with the terms of the budget resolution.

(Discretionary spending is approved by Congress each year.)

The discretionary total will eventually be divided by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees between the 12 subcommittees, each responsible for a single annual spending (appropriations) bill.

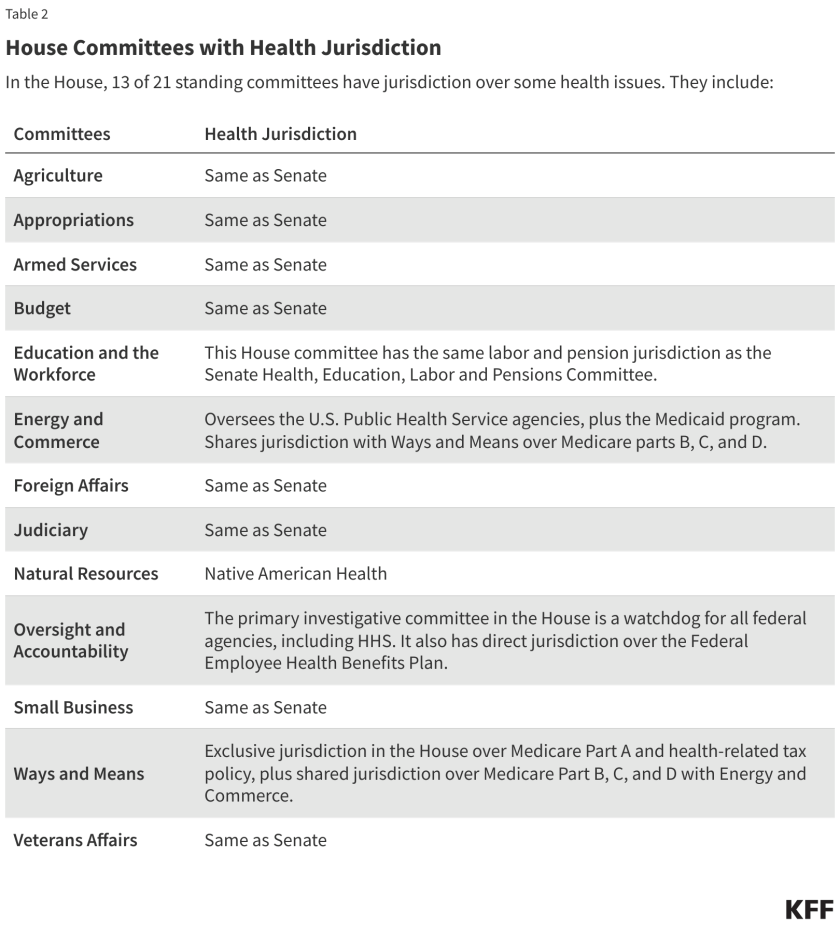

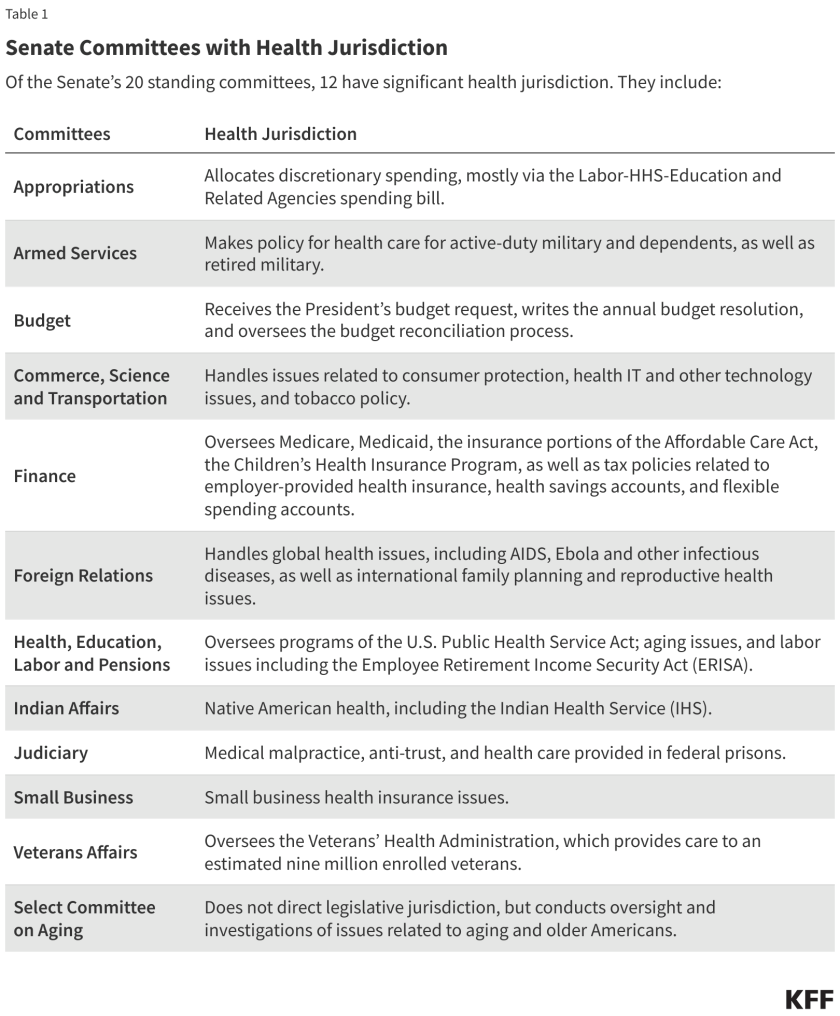

Refer to this previous post for lists of the Congressional Committees and what they oversee.

Most of those bills cover multiple agencies – the appropriations bill for the Department of Health and Human Services, for example, also includes funding for the Departments of Labor and Education.

After the budget resolution is approved by each chamber’s Budget Committee, it goes to the House and Senate floors for debate.

Assuming the resolutions are approved, a “conference committee” comprised of members from each chamber is tasked with working out the differences between the respective versions. A final compromise budget resolution is supposed to be approved by both chambers by April 15 but rarely happens.

Because the final product is a resolution rather than a bill, the budget does not go to the President to sign or veto.

The Appropriations Process

The annual appropriations process kicks off May 15, when the House starts considering the 12 annual spending bills for the fiscal year that begins Oct. 1. By tradition, spending bills originate in the House, although if the House is delayed, the Senate will take up its version of an appropriation first.

The House completes action on all 12 spending bills by June 30, to provide enough time for the Senate to act, and for a conference committee to negotiate a final version that each chamber can approve by October 1, the only deadline with consequences if it is not met.

Avoiding a government shut-down

Unless an appropriations bill for each federal agency is passed by Congress and signed by the President by the start of the fiscal year, that agency must shut down all “non-essential” activities funded by discretionary spending until funding is approved. (The so-called government “shut-down” that we hear about.)

A CR (Continuing Resolution) can last the full fiscal year and may cover all of the federal government or just the departments for the unfinished bills.

Congress may pass multiple CRs while it works to complete the appropriations process.

An Omnibus Measure

While each appropriations bill is usually considered individually, to save time (and sometimes to win needed votes), a few, several, or all the bills may be packaged into a single “omnibus” measure. Bills that package only a handful of appropriations bills are cheekily known as “minibuses.”

Reconciliation

Meanwhile, if the budget resolution includes reconciliation instructions, that process proceeds separately. The committees in charge of the programs requiring alterations vote on and report their proposals to the respective budget committees, which assemble all changes into a single bill. (which the budget committees may not change.)

- Reconciliation legislation is frequently the vehicle for significant health policy changes.

- Reconciliation bills are subject to special rules, especially in the Senate including debate time limitations (no filibusters) and restrictions on amendments.

- Reconciliation bills may not contain provisions that do not pertain directly to taxing or spending.

Unlike the appropriations bills, nothing happens if Congress does not meet the Budget Act’s deadline to finish the reconciliation process, June 15. In fact, in more than a few cases, Congress has not completed work on reconciliation bills until the calendar year AFTER they were begun.

Rovner, J., Congress, the Executive Branch, and Health Policy. In Altman, Drew (Editor), Health Policy 101, (KFF, January 2025) https://www.kff.org/health-policy-101-congress-and-the-executive-branch-and-health-policy/ (February 14, 2025).

. comp by Zimmerman, Marie, Active 1915 [Philadelphia, Pa.: E.M. Zimmerman, ©, 1915] Notated Music. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2017562229/>.

Exploring the HEART of Health

If you made it this far, congratulations! This is not easy to absorb so I thank you for choosing to inform yourself about what happens after we vote.

The illustrations on this post are from the Library of Congress, Free to Use and Reuse site, believed to be in the public domain.

I’d love for you to follow this blog. I share information and inspiration to help you transform challenges into opportunities for learning and growth.

Add your name to the subscribe box to be notified of new posts by email. Click the link to read the post and browse other content. It’s that simple. No spam.

I enjoy seeing who is new to Watercress Words. When you subscribe, I will visit your blog or website. Thanks and see you next time.